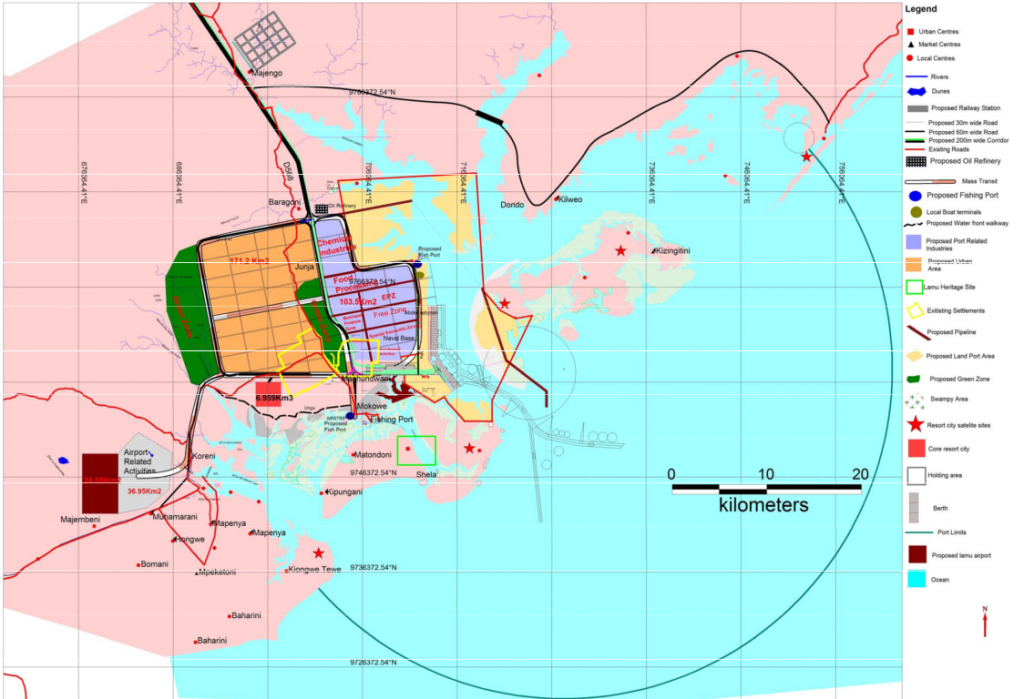

Since 2009, the Government of Kenya (GOK) has expressed plans to undertake a multipurpose transport and communication corridor known as the ‘Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor. LAPSSET will consist of a standard gauge railway line, a port, a super highway, a regional international airport, an ultra-modern tourist resort, an oil pipeline, and a fibre-optic cable constructed to link Lamu to Juba and Addis Ababa. Through the media, we have found out that about the GOK’s push for the launching of the project despite our lack of knowledge of the proposed plans, project feasibility, or environmental impacts.

The initial plans for the Lamu Port were based on a 1977 feasibility study carried out by the then Ministry of Power & Communications. It is estimated that the Lamu port will cost more than $5 billion. Late 2010, a feasibility study by Japan Port Consultants of Tokyo for the Port was financed by China, which is yet to be shared with the general public. Despite the community’s lacking awareness and failing to be consulted, we learned from the media on July 26th, 2011, that the President gave the go ahead with the project. Worse yet, the president’s go-ahead is prior to carrying out an environmental impact assessment to help determine the mitigation plan needed. Considering the fragility of the local ecosystem on which the Lamu communities are highly dependent on, this would be a great oversight on the part of the GOK and the project financiers.

1. Environmental Impacts (Article 42)

Lamu is endowed with rich biodiversity and has some of the richest marine ecology on the Kenyan coastline. Unfortunately, many of the wildlife lie close to proposed Lamu Port site, while coral reefs that are a major tourist attraction in the area are in the heart of the Manda Bay site where the ships would have to sail through to get to the proposed port. The shores are lined with mangrove forests, where fish are known to breed in plenty. The feasibility study carried out by the Japan Port Consultants Ltd in 2010 clearly spells out that the Lamu port will have extensive effects on both marine and terrestrial life, and establishes that an EIA is essential before the initiation of the construction of the port as stipulated by the Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) 1999. However, to date, no EIA has been carried out by the Government, furthermore following the guidelines of the EMCA Act, not consultations have been carried out.

2. Community Participation (Article 69)

Section III (17.l) of the EMCA 19999 further emphasizes that, “during the process of conducting an environmental impact assessment study under these regulations, the proponent shall in consultation with the Authority, seek views of persons who may be affected by the project”. The feasibility study further specifies that a minimum of two stakeholder forums must be carried out. However, since the GOK expressed plans to undertake the LAPSSET multipurpose transport and communication corridor in 2009, the government only carried out a sensitization meeting with stakeholders, but none with the affected communities yet the work has commenced.

3. Access to information (Article 35)

Despite the significant impacts expected by the port and the scale of the project, there has been limited information provided to the people of Lamu. Information has been restricted to the Provincial Administration and select community leaders and government officers in Lamu and Nairobi high offices. A committee for the port was only just formed on the last week of January 2012 after the GOK already ploughed through farms to make way for the port area. To further exemplify the “secrecy” behind this project, the Japanese Port Consultants contracted to for the port feasibility study has declined to provide information on their contract sum and the tendering process to the parliamentary committee on Transport, Public Works and Housing, thus depriving Kenyans the information on the fiscal implications of the project.

4. Social Impacts (Articles 11 and 44)

Lamu is one of the poorest Counties in Kenya with a populationg of 101,000. The minority community are the indigenous Bajun, Orma, Sanye and Aweer who are a marginalized community in Kenya having very low education levels. A majority of the communities still depend on nature-based livelihoods such as: fishing, mangrove cutting, hunting and gathering, pastoralism, farming, eco-tourism operators, and many others. It has been predicted by the 2010 feasibility predicts that the population in Lamu will increase to over 1.25 million people over the period of construction, more than the population of Mombasa town. While we acknowledge the freedom of Kenyans to live in any part of the nation as accorded in the constitution, the same legal document also mandated the protection of indigenous communities and cultures. In view of Lamu’s unique cultures that form the core of its designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the failure of the government to put in measures into place that preserve the indigenous cultures will threaten the bio-culture of the region. Despite the feasibility study outlining the Archaeological Impact Assessment and creation of development policy as fundamental steps prior to the construction of the port, to date, no efforts to towards implementing these has been made.

Farmer, Omar Shee, infront of his farm house and road cutting through his farm at Kililana without being compensated or resettled

5. Land Tenure Insecurity (Articles 60-63)

As previously mentioned, plans on the port have been maintained internally amongst the inner circles of government for several years. As a result, individuals with access to the plans have been scurrying to obtain land at the proposed development sites while locals remain internally displaced without any title deeds. The government has proved its disregard for the rights of the local communities by tearing through farms in Kililana area in January 2012 to prepare for the port launching site without informing, compensating, or relocating those affected although the feasibility study also spells out the need to create a resettlement action plan (RAP). The feasibility study also directs that the boundary of the Lamu port should be enacted into the National Land Bill. The GOK claims that the land on which the port is to be constructed falls on government land despite the fact that the constitution clearly spells out that the land to be partially community land to be managed by local communities, and public land which is vested in the County Government, administered by the National Land Commission. Considering that the National Land Bill has not been created, nor is the County Government in place, it would be prudent for the GOK to wait until such a time for the port land boundary to be clearly defined before initiating the project. Not doing so reveals suspicious motives and serves to perpetuate the already sensitive nature of land tenure insecurity in the area.

In addition to the laws spelled out above, by its irresponsible actions, the GOK clearly violates principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development which recognizes that: “At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available…”

Although we agree that Kenya as a country and East Africa as a whole will stand to benefit from the port, we are in doubt that economic development on the one hand, and the ecological, social, cultural and economic destruction of the Lamu archipelago and its indigenous communities on the other, is a reasonable ‘trade-off’. We anticipate that based on your responsibility to oversee the achievement of good governance and improved service delivery of local authorities, you will be able to direct the respective government bodies to act in accordance to the laws of Kenya by suspending of the port construction until the above concerns are addressed by the GOK.